In Femenine as in life, one mood seldom lasts. The way the weeping flugelhorn and enraged vocals intertwine with one another, and with the effervescent little orchestra around them, mimics the way that at any given moment, whatever feeling is most pronounced is always pitted against whatever else might be bounding through your brain. Set against rhythms that are as regular as a heartbeat yet flit like an anxious mind, these improvisations collectively suggest a life’s complicated emotional range.

#Julius eastman crack

Singer Odeya Nini grunts and wails, redlining her crystalline soprano until it could crack glass she inhales pain to exhale it with fury. Marta Tiesenga’s baritone saxophone later writhes like a wounded animal, grasping for any shred of comfort but finding none.

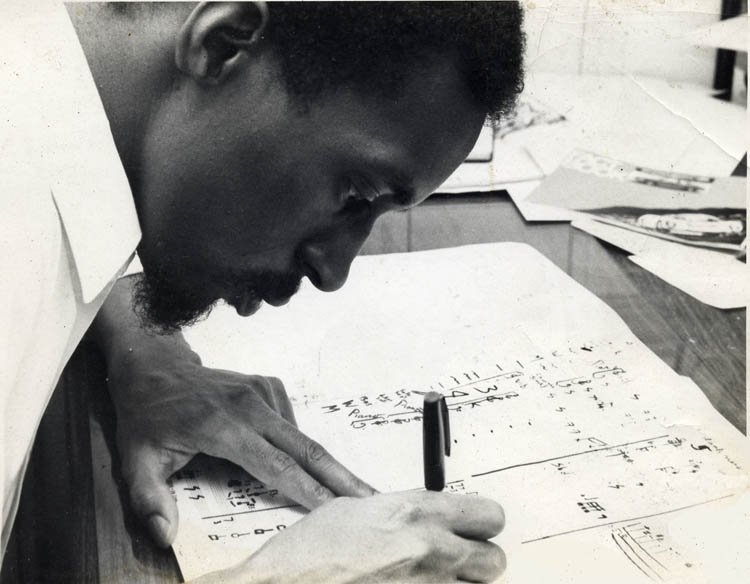

Near the top, pianist Richard Valitutto drifts through autumnal variations so bittersweet they suggest a Bruce Hornsby hymn warm and sad, his notes offer an apology to Eastman, a tender promise that his short life will relish a long tail. Nine soloists improvise against the basic structure. Wild Up push the flexibility Eastman wrote into Femenine to its extreme. The music’s emotional dynamism has a pull like that of a particularly absorbing film. Femenine works a little like GAS, gamelan, or any other iterative music: The details wedged into the recesses of these repetitive rhythms are what give it power. Tune out for a second, and a hundred notes seem to whiz past. The rest of Femenine is a dizzying dance of flutes and whistles, violins and synthesizers, piano and voices, which all take the form of perpetual motion machines. These double ellipses suggest we’ve heard but a sample of a saga with no beginning or end, glimpsing a cycle that will soon resume. Both persist for the entire piece, gradually fading out toward the end. A vibraphone soon joins, its enchanting melody instantly indelible. A choir of sleigh bells rings when Femenine begins, amassing like cicadas at the start of a summer night. With a cast of 20, Wild Up run with this mere suggestion of direction: On record, Femenine has never sounded more vital, immersive, or necessary.Ī play-by-play accounting of this or any version of Femenine can go one of two ways: Very little happens or changes for the entirety of these 70 minutes, or so much happens in the course of just 30 seconds that trying to chronicle it all would be tantamount to documenting your body’s every skeletomuscular twitch. Eastman’s loose score works more as a suggestive framework, allowing whatever musicians are playing Femenine to take liberties with everything besides its rhythms. Femenine stands among these pulsating minimalist landmarks but also apart from them.

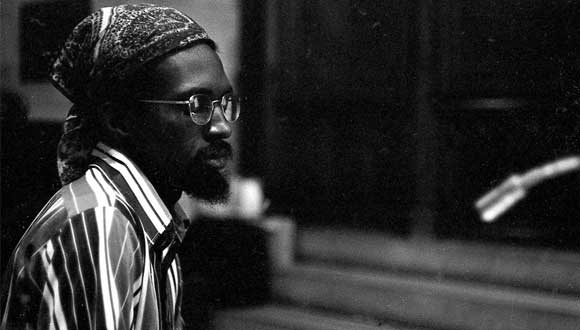

Eastman premiered Femenine in 1974, the same year Steve Reich began writing Music for 18 Musicians and Philip Glass unveiled Music in 12 Parts, three years before Rhys Chatham conceived Guitar Trio. They begin with Femenine, the work that has not only been the most publicized for years now but is also something like Eastman’s thesis, the piece where so many of his interests and loves collide in a transcendent hour of nonstop sound. They intend to spend the next six years arranging, recording, and releasing an exhaustive seven-volume anthology of the Eastman pieces that survived his piteous end. No organization has committed more fully to this public reintroduction than Wild Up, a radical California chamber collective of composers, performers, and improvisers whose imagination and ambition seem boundless. The New York Times even gave this groundswell a name: Eastmania. The Los Angeles Philharmonic paired Eastman’s music with that of Arvo Pärt in August, while the New York Philharmonic will present his work in January, a reappraisal that might have astonished the hometown provocateur. Over the past decade-plus, there have been a book, a trio of box sets, a DJ/rupture tribute, major newspaper profiles, and multiple versions of Femenine by chic new music ensembles. But especially since Frozen Reeds’ indispensable 2016 excavation of his early-’70s masterwork, Femenine, Eastman has seemed newly omnipresent, vaunted not only for his ecstatic minimalism but also for his prescient rejection of genre and high/low divides.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)